Making Sense of Bonds

“Why are my bond returns negative? Isn’t this the defensive part of my portfolio? If inflation is rising and interest rates are about to go up, should I be in bonds at all?” Fixed interest, usually in the shadow of shares, is suddenly at the centre of investor concerns.

It’s true most people rarely think about the bond market. It certainly doesn’t get much attention on the nightly finance news, particularly in comparison to the daily ups and downs of the share market and stories about individual companies!

But the bond market is actually a big deal. According to the Global Financial Markets Association, the outstanding value of global bond markets in 2020 was $US123.5 trillion, exceeding the global equity market’s $105.8 trillion capitalisation.1

To get to grips with what’s happening in the bond market and what it means for everyday investors, let’s go back to basics for a moment:

Bond Basics

Bonds and shares have some things in common. They’re both types of securities used by companies to raise capital. They are both initially offered in the primary market and traded in the secondary market. There are risks and premiums associated with both. And their prices go up and down on news.

But bonds and shares also differ in key ways. While shares are a form of ownership, bonds are a type of loan issued for a set maturity – from less than one year to 30 years or more. Unlike shares, bonds are issued by governments as well as by companies. Finally, bonds tend to be less volatile than shares.

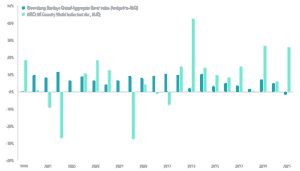

This last point of differentiation means bonds are referred to as defensive investments, used to temper the volatility of an overall portfolio. In years with sharp share market drawdowns – like we saw in 2002, 2008, 2010 and 2011 and most recently during the pandemic-related volatility of March 2020 – bonds acted as a kind of buffer.

EXHIBIT 1

Global Bonds Vs Global Shares

Another key difference with bonds is they offer more information about future cash flows. Yes, their prices go up and down like shares. But they also offer a fixed income stream via their coupon, which is the annual interest paid on the bond.

Bonds are most often compared by their yield. This is the expected total return of the bond based on its price today and assuming it is held to maturity. Bond prices and yields move inversely. So, all else being equal, the expected return or yield of the bond rises when the price falls, and vice versa.

Recent Markets

Since bond yields in many cases hit record lows at the onset of the pandemic two years ago, they have risen significantly. In the case of Australian Government 10-year bonds, the yield has risen from about 0.6% in March 2020 to more than 2% recently.

In 2021, a global benchmark for bonds – the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond index (hedged to Australian dollars) – posted its first calendar year negative return since 1994. While this was unusual, it was neither unexpected nor unprecedented. And keep in mind that global shares last year delivered returns of about 30% in AUD terms.

As we mentioned, bonds are still risky assets. The two key risks are term, which relates to the bond’s sensitivity to changes in interest rates, and credit, which relates to the likelihood of the bond issuer defaulting on the debt. The losses from bonds in 2021 related overwhelmingly to the first of these risks – term.

Bond yields, or market interest rates, have risen in the past year amid an environment where market expectations for variables like economic growth or future inflation have changed – in some cases dramatically.

The Role of Central Banks

Much of the media commentary about bonds relates to speculation about how fast and by how much central banks will act against rising inflation by lifting their benchmark rates from near zero. The Reserve Bank of NZ has already started lifting its official cash rate, although the RBA has said it is in no hurry to move.

That’s fine as far as it goes. But it’s important to understand that in adjusting rates, markets tend to move well ahead of central bank benchmarks anyway.

For instance, the RBA during the peak of the crisis in March 2020 set a target for the yield on three-year Australian Government bonds of around 0.25% – the same as the cash rate. This was later cut to 0.1%. It achieved this by buying government bonds in the secondary market.

By November, 2021, however, the RBA had to drop the target of 0.1% for the three-year bond because the market had already driven the bond yield well above that figure.

While the Australian central bank has said it is in no hurry to raise official cash rates because of an uncertain economic climate, the market – as measured by 30-day interbank cash rate futures – has already priced in the cash rate rising to 1% by the end of 2022.2

Of course, those expectations could change depending on future news of growth and inflation. The market and central banks have access to the same information. The difference is the market reacts to news in real-time and prices securities accordingly.

Lessons for Everyday Investors

So what does this all mean for a diversified investor? First, just because short-term interest rates rise does not necessarily mean that bonds will underperform. We have evidence that in past episodes of rising short-term rates, there has been no consistent pattern. On some occasions, long-term bonds have rallied as short-term bonds have underperformed.

Second, we have seen that the bond market, like the share market, is forward-looking. Bonds price in expectations for interest rates and inflation. In October last year, for instance, we saw Australian bond yields rise sharply after a higher-than-expected local inflation report.3 But if expectations change, prices can change. Predicting how expectations will change means being able to predict the news and how markets will react. Economists’ record on that front isn’t great.

Third, while we can’t forecast rates, we do have information in today’s market. We know the income we will receive by holding the bond to maturity. And we know the expected capital gain for holding the bond for a set period based on today’s conditions. We can use that information to build portfolios for different needs – whether it be to generate return, to dampen volatility, to provide liquidity or protect against inflation.

Finally, we can diversify. Not every country’s bond market moves in the same way. Inflation is at a 40-year high in the US, but not so in Australia. There are different opportunities across the globe. That means we can position ourselves where the expected returns best suit our goals.

In summary, bonds still have a part to play in a diversified portfolio. They behave differently to shares, are less volatile and can offer stability during down markets for equities. Bonds carry their own risks, but we can deal with those via diversification and discipline. While yields have risen from historic lows, higher yields mean lower prices and can represent opportunity for future returns.

FOOTNOTES

- Capital Markets Fact Book, 2021, SIFMA.

- ASX 30-Day Interbank Cash Rate Futures – Implied Yield Curve, Australian Securities Exchange, 11 Feb, 2022.

- RBA Faces Pressure to Intervene Again on Yields After CPI Surge’, Bloomberg, 27 Oct 2021.

Next steps

If you have any questions/thoughts in relation to this article or would like more information, please contact Gordon Thoms or David Conte at Calibre Private Wealth Advisers on ph. (03) 9824 2777 or email us here.

The information contained in this article is of a general nature only and may not take into account your particular objectives, financial situation or needs. Accordingly, the information should not be used, relied upon or treated as a substitute for personal financial advice. While all care has been taken in the preparation of this article, no warranty is given in respect of the information provided and accordingly, neither Calibre Private Wealth Advisers, its employees or agents shall be liable for any loss (howsoever arising) with respect to decisions or actions taken as a result of you acting upon such information.

This advice may not be suitable to you because it contains general advice that has not been tailored to your personal circumstances. Please seek personal financial and tax/or legal advice prior to acting on this information. Before acquiring a financial product a person should obtain a Product Disclosure Statement (PDS) relating to that product and consider the contents of the PDS before making a decision about whether to acquire the product. The material contained in this document is based on information received in good faith from sources within the market, and on our understanding of legislation and Government press releases at the date of publication, which are believed to be reliable and accurate. Opinions constitute our judgment at the time of issue and are subject to change. Neither, the Licensee or any of the Oreana Group of companies, nor their employees or directors give any warranty of accuracy, nor accept any responsibility for errors or omissions in this document. Gordon Thoms and David Conte of Calibre Private Wealth Advisers are Authorised Representatives of Oreana Financial Services Limited ABN 91 607 515 122, an Australian Financial Services Licensee, Registered office at Level 7, 484 St Kilda Road, Melbourne, VIC 3004. This site is designed for Australian residents only. Nothing on this website is an offer or a solicitation of an offer to acquire any products or services, by any person or entity outside of Australia.